Against the Grain: Skate Culture and the Camera opened in Soho London earlier this month. The show, which celebrates 50 years of skateboarding, had a two-and-a-half week run and featured photography from iconic photographers including J. Grant Brittain, Dobie Campbell, Glen E. Friedman, Spike Jonze, Sam Muller, Skin Phillips, Tobin Yelland and Matthew “Wig” Worland, among others. It also housed video installations from Steve Douglas (411VM), Winstan Whitter, Graham Fletcher-Cook and again, Spike Jonze.

“There have been so many films about skateboarding and everyone tends to have their favourite period depending on when they discovered skateboarding. But I thought it would be nice to tell it from a different perspective and link different histories,” says Jaime Marie Davis, the co-curator of the exhibit.

“There’s always been so much focus on skaters, and rightly so, but not enough recognition has been given to photographers who are the people, in some ways, that have circulated information about skateboarding. There’s a symbiotic relationship” says Davis. “Photography was an important part of developing the scenes and culture.”

Davis grew up in San Diego watching her brother and his friends skate. While she was more of a surfer, skateboarding was always something she connected to. Partnering with Frankie Shea, founder of Moniker Projects and London’s Moniker Art Fair, the two eventually locked down enough artists to participate in the show. Although they do wish they could’ve shown more. Luckily the exhibition will be coming to North America in 2019 and Tokyo in 2020.

Photo by Glen E. Friedman, Hangin at Adolph’s in Holmby Hills, 1977

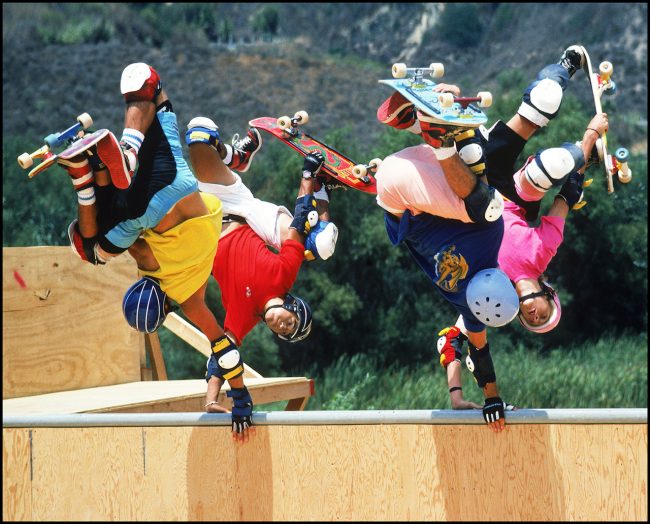

Photo by J.Grant Brittain, Bones Brigade, Chin Ramp, 1986

Photo by Dobie Campbell, Palace Originals, Lucian Hendricks, Crystal Palace, 1985

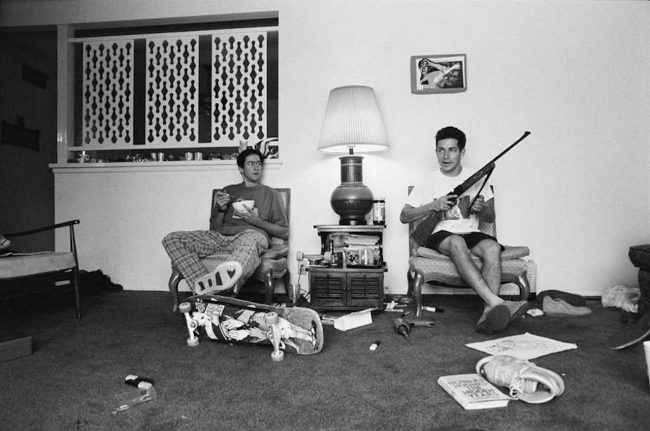

Photo by Tobin Yelland, John Cardiel and Slayer poster, San Francisco, 1991

“There are so many photographers missing from this exhibition as well as skaters and that’s why I think it’s so important to have it tour so it can grow and focus on other photographers in other areas,” explains Davis. “I mean there’s people missing even from London like Sam Ashley, who because of timing and travelling we couldn’t make it work. He is so important to London’s culture.”

Much of the work scurries between solo pics and culture shots, highlighting the synergy between lens and location, subject and beholder. The connection between skateboarder and photographer is key as often the two are friends, scouting spots and taking the time to get the right shots, together.

“I thought the relationship was interesting and important to focus on. I wanted to talk about the evolution of skateboarding. And to think about the evolution of film and photography and how those changes influenced the way skateboarding was portrayed,” says Davis.

At first many of the photographers were cautious because “they wanted to be sure I understood what I was doing before they were being represented by another voice,” explains Davis. “But there were some like Skin [Phillips] and Sam Muller that just kind of understood the place I was coming from and what I was trying to do. They trusted I knew what I was talking about.”

“My aesthetic is about a collective ethos. I’ve been part of collectives such as the current Hemera Collective and the struggle is always how to remain an individual and also maintain collective interests,” says Davis. “I think skateboarding really reflect this. You can be recognized for individual achievements but yet still hold strong to supporting the larger family of skateboarding.”

Matthew “Wig” Worland is a veteran skateboarding photographer based in London, and some cite him as “the first person to properly bring the studio to the street” as well as the “Governor of British skateboarding photography” whom shot for both Transworld and Sidewalk magazines.

A BMX biker-turned-skateboarder, Worland picked up the sport but realized he wasn’t “ever going to be particularly good at it” but he loved watching the moves happen and the individual style of the skateboarders around him. “I thought I could capture that,” says Worland. “Perhaps an analogy would be: I’m a fantastic dancer so I haven’t felt the need to photograph dance. Yet, anyway.”

“Shooting skateboarding is pretty much always a collaboration between the skateboarder and the photographer, and ‘skateboard photographers’ are quite often skateboarders themselves. They usually have an understanding of where the action will happen so there is usually no danger of collision,” he adds. “One of the great things about photographing skateboarding is how close you can get to it. You can’t get that close to any other ‘sanctioned’ sport or team game. You couldn’t run around on a football pitch to shoot a football without interfering with the game.”

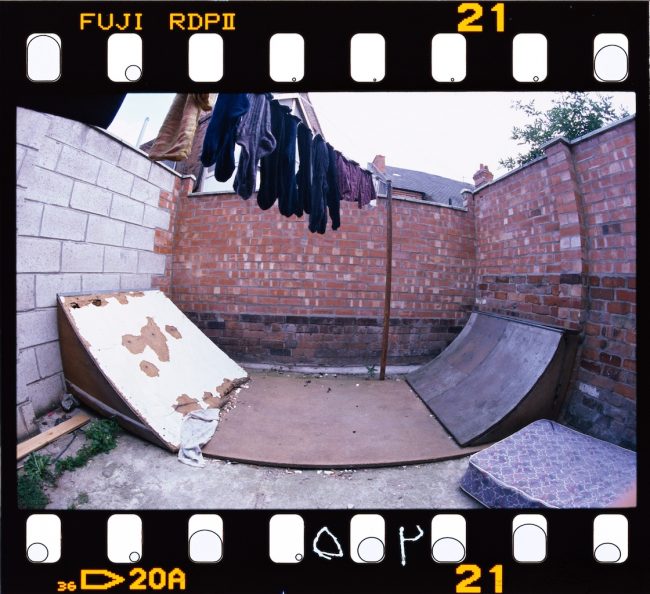

Worland’s style of shooting has set him apart; his attention to lighting is interesting to note. “I lived in a dark and dingy country but interestingly when I did have the opportunity to work in sunnier places like Southern California or Spain, I would choose to wait until the evening to shoot as at that time I would then have more opportunity to control the light and to make the pictures how I wanted them to be. Flash-lit and surrounded in light rather than overpowered by the sun,” he says.

Photo by Wig Worland, Scott Underdown’s backyard, Nottingham, 1995

He also had legends like Grant Brittain encouraging him.

“I remember calling up Grant Brittain at TWS [TransWorld SKATEboarding] in the early ’90s and telling him I had worked what I wanted to do and that I needed to get some ‘radio slaves’. These are remote control devices that help the camera communicate with the lights and they work via radio waves,” explains Worland. “It’s much better for shooting action as you no longer had wires trailing everywhere. He got on the phone to the local camera store and told me to go and pick them up. That was it. I was off.”

Sam Muller, whose below photograph was taken in Montreal’s Mount Royal area, grew up in Los Angeles practically three minutes from the most famous skate spots, Hollywood High. Muller was interested in the sport but he says “he kinda sucked at it” no less. After playing around with a friend’s dad’s video camera and being that his own father was a hobbyist photographer, Muller soon became summoned to the streets to shoot.

“Skateboarders are pretty habitual; we’ll skate the same places over and over and over again until we can’t anymore and then we’re like ‘ah guess it’s time to go and find a new spot’,” says Muller. “Half the battle is exploring and figuring out where and what we’re going to do. I feel like a lot of skate photographers and filmmakers wanted to be professional skateboarders before they picked up a camera.”

Photo by Sam Muller, Untitled, Christian Maalouf, 2015

For his photograph of Christian Maalouf, Muller tells us the story.

“He was trying a trick down the four stairs, something simple like nothing crazy at all and he kept bailing really crazily. So I just sat there as close as I could without bothering him too much. It wasn’t super dangerous for him and I composed and just waited for him to fall through my lens,” says Muller. The extension of the torso, his back-breaking bail, the blood-tinged scratches—all these details show the body-to-pavement aspect of skateboarding.

“They really are risking life and limbs to do what they love to do,” adds Muller.

For Muller, shooting skateboarding is “ideal first thing in the morning” but regardless of what time “you really gotta dedicate the day to the skateboarder because sometimes you go to three locations and don’t get anything so even though you’re a little frustrated you can’t just leave. You’re in it for the day.”

“I really like shooting and skateboarding in the American Southwest,” he says while also citing New York and Los Angeles as other favourites.

“In New York there’s so much going on, so many outside influences on how the actual skateboarding happens. You’re dodging people all the time and you gotta be aware of police. It’s way more rugged in New York than it is in LA, the birthplace of skateboarding.”

Skateboarding is often met with notions of rebellion and mischief, but Muller thinks now that the sport has been added to the lineup at the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo, more people could start to see it as a competitive sport like any other.

“I’m curious to see once that happens and people see it is an Olympic sport well maybe they won’t understand it anymore than they already do, but maybe they’ll think ‘oh what you’re doing is legitimate because it’s in the Olympics so hey maybe we’ll give you less of a hard time’. I think that may be wishful thinking though,” he says with a snicker.

Against the Grain also featured a selection of zines, some from the curators themselves and others snagged up at local shops, venues and so on. Selections from Transworld, R.A.D. and Thrasher were all on hand.

Photo by Spike Jonze, Jason Lee and Mark Gonzales, Huntington Beach, 1989

Onlookers spent approximately 40 minutes at the exhibit, according to Davis, and in the morning she often showed up to the space with at least 10 people waiting to check it out.

There was a compilation of Spike Jonze’s videos presented too, from “Video Days” (one of the most influential videos of the genre) to bits on Girl Skateboards, the company Jonze founded in 1993 alongside Rick Howard and Mike Carroll.

Below photos by Tom Vera

The runtime of the exhibit for Davis was too short though. She wishes there was more time for the public to take it all in.

“I’m a really big believer of long-run exhibitions. I mean there’s a certain appeal for the of the moment pop-ups or one-week events but in general, I like long-run,” says Davis. “A lot of effort goes in by people to put together an exhibition no matter how big or small it is. Sometimes it’s nice when there’s a small performance that is a moment in time, but I think all exhibits should be two months long so people can get down and see it.”

As for other skateboarding photographers to check out? Matt Price and Trent Parke are two of Worland’s favourites.

On Parke: “He’s the person I most like in the photography world. He manages to photograph reality but brings about a sense of the unreal. Like you are looking into another dimension and seeing something you usually can’t. I only wish I had the patience to do it myself. It’s truly amazing.”

On Price: “He’s the guy that gets really close.”

Opening event photographs taken by Alexander Christie.

To me photography, it’s a craft and I’ve been lucky enough to be able to earn a living from it. Splitting hairs? Probably.

– Matthew “Wig” Worland